Last year, through her Goyen Literacy Fellowship, reading interventionist Catlin Goodrow shared her work in a series of informative and resource-ful Twitter/X threads. This summer, in attempt to give them a semi-permanent home, we are going to reshare them on this blog. First up: paragraph shrinking. And if you like Catlin’s work, pre-order her book about supporting older elementary school students work with complex texts!

I have had so many teachers tell me kids struggle with "main idea." The strategy I’m going to write about today provides scaffolds so kids can be successful. Below, I lay out how I use gradual release to teach this strategy.

A note before I begin, this strategy is called "paragraph shrinking" in peer-assisted learning strategies (PALS); it’s called "get the gist" in collaborative strategic reading (CSR). They are very similar. I usually call it "get the gist."

The first step of the strategy is to identify "the most important who or what" in a paragraph or section of text. I usually begin this orally, modeling with think-alouds and giving feedback as kids try it.

Paragraph shrinking is often done orally, but I have students write it out, as a simple way to take notes across a knowledge-building unit or longer text.

The second step of the strategy is to identify "what's most important about the who or what?".

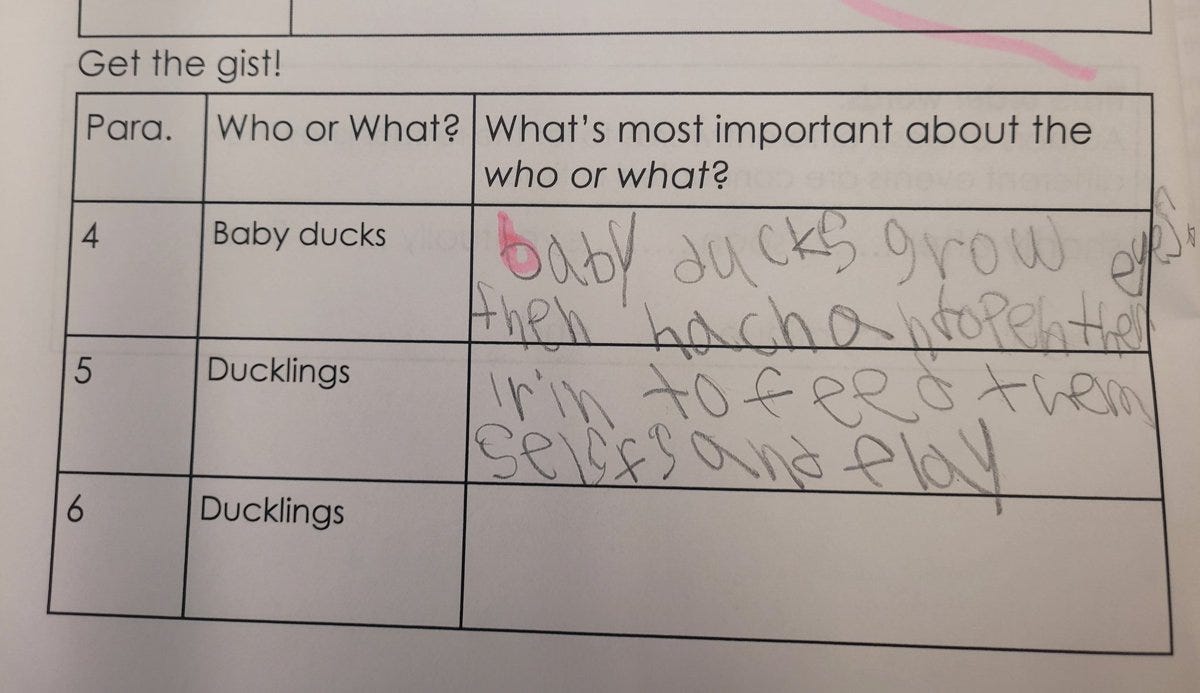

I begin by providing a 3-column table - sometimes with the "who or what" provided, so students can focus on what's important about it. At this phase, students often riff on info from other parts of the text. Feedback and modeling can help them focus.

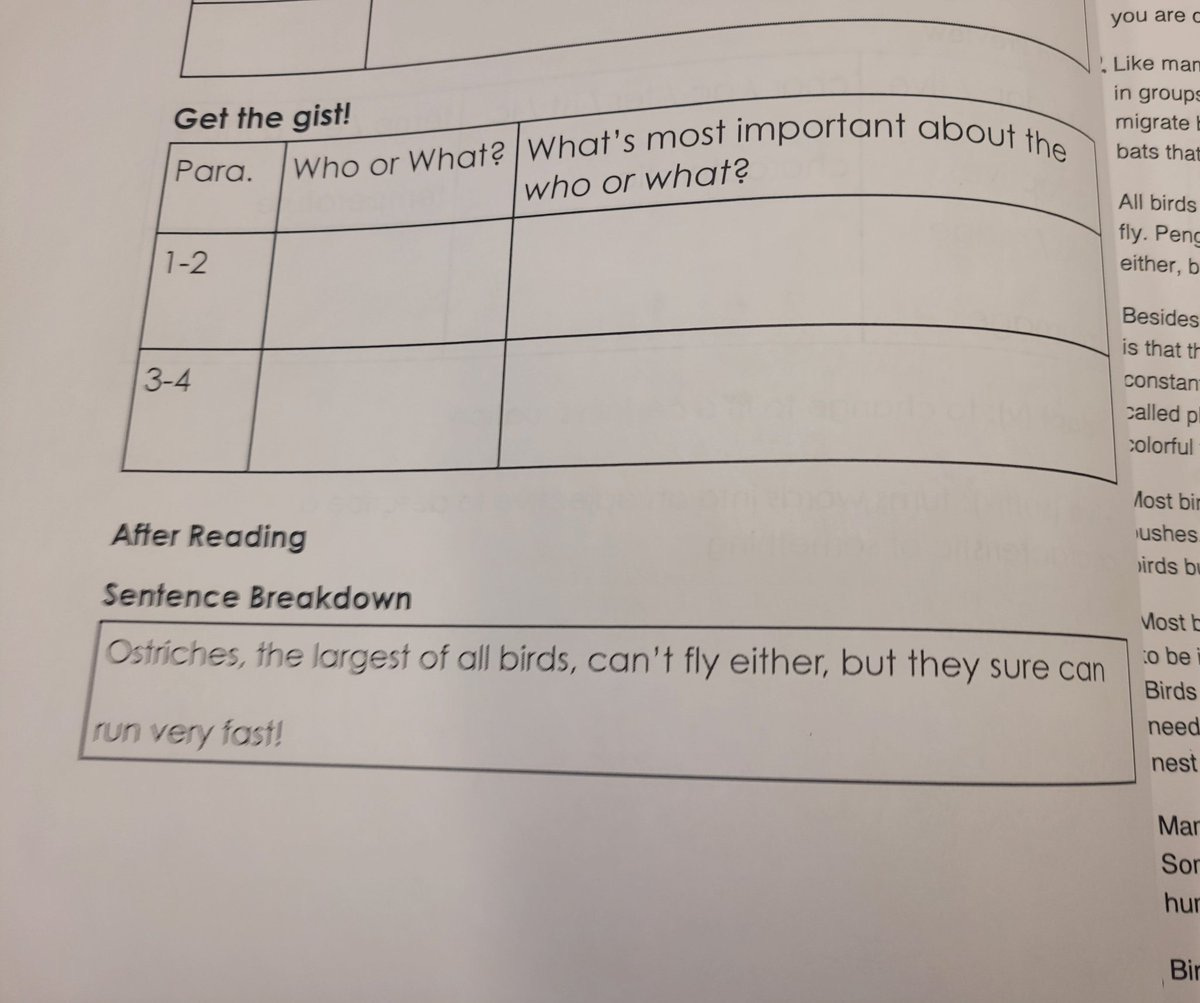

I then have students independently identify the "important who or what" and "what's most important about it" in the 3-column table.

At this point, I find that students often spontaneously begin writing main idea sentences in the third column of the table. But if they do not, I add an intermediate scaffold to transfer their work in the table to a sentence.

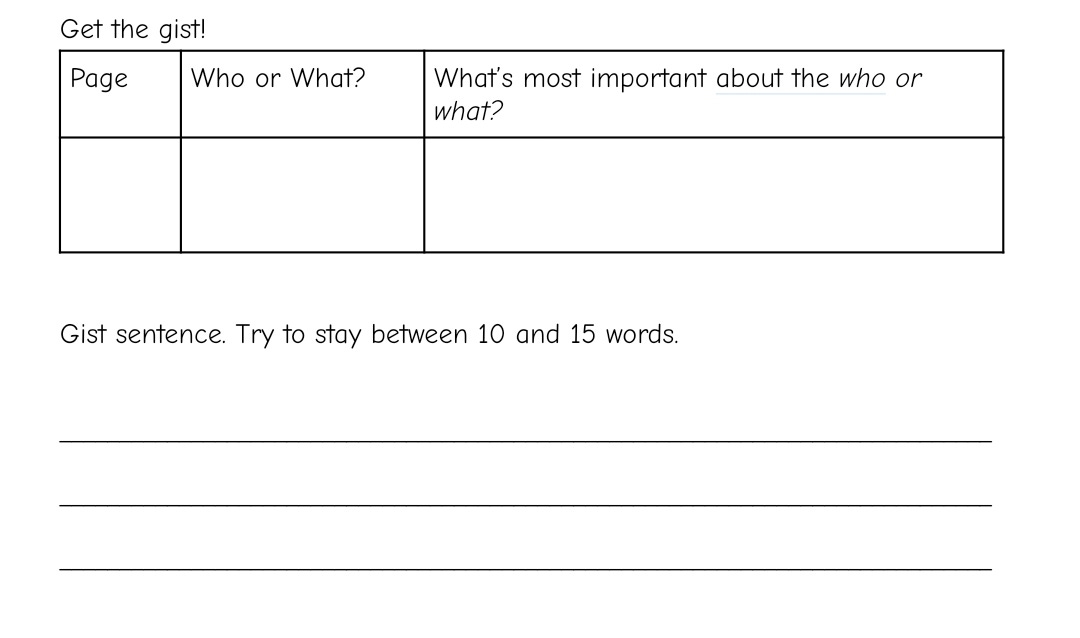

The final step? Students write a main idea sentence without the scaffold of the 3-column table.

Read more about paragraph shrinking here.

Thank you for writing and sharing such a clear, replicable structure. It’s the kind of routine that can make a real difference in everyday instruction. When I’m partnering with school districts, one area we often spend extra time on—especially in the early grades—is helping students determine what’s most important. That distinction between “my favorite part” and “the most important part” isn’t always intuitive. We work on noticing repeated words, looking for topic sentences, and in narratives, using the problem and solution as clues. Identifying the most important information often requires its own set of strategies and lots of guided practice—but it’s foundational work that pays off across reading and writing.